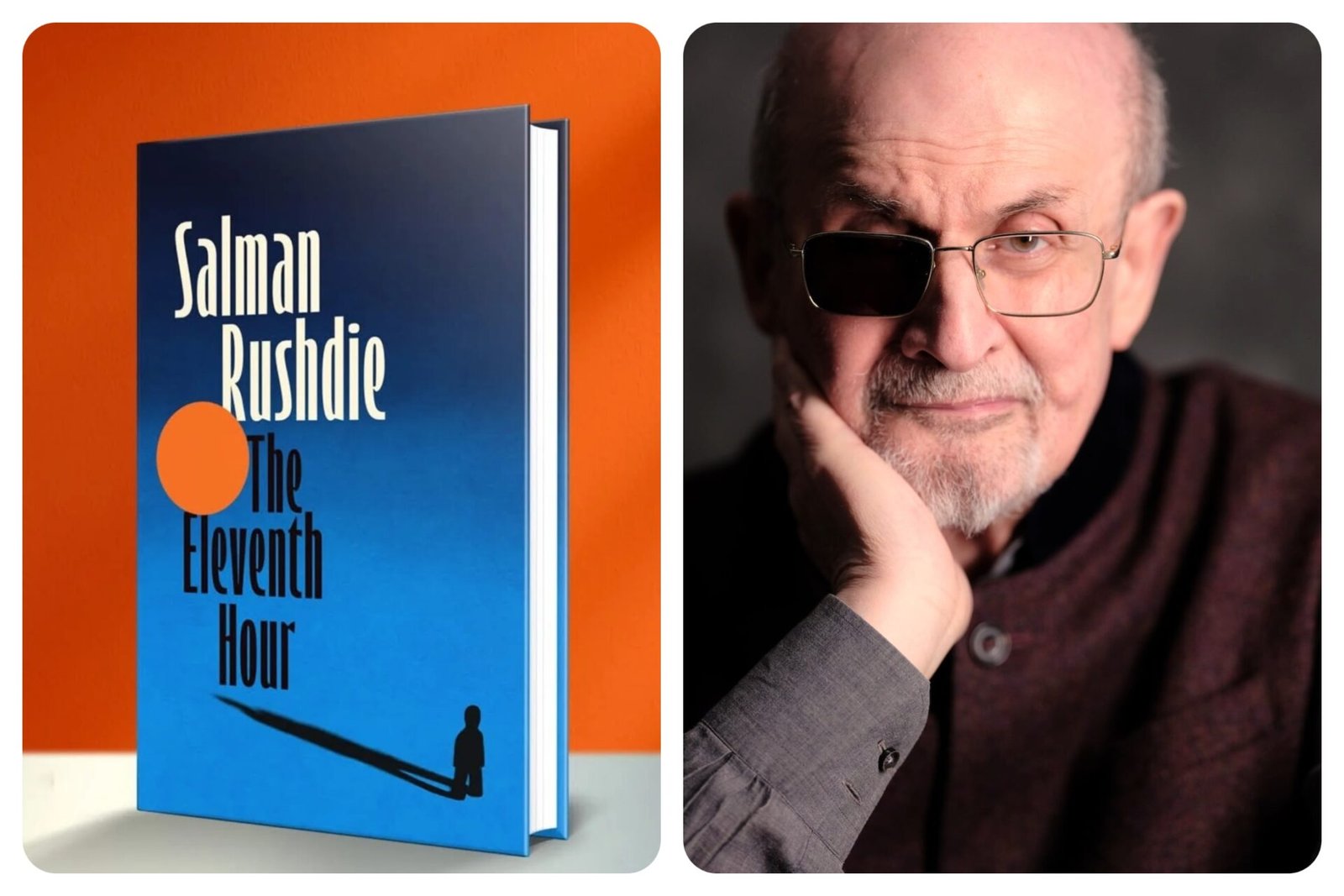

Salman Rushdie’s The Eleventh Hour is elegantly written and movingly elegant, and the difference between those two qualities is the quiet tension at the heart of the book. This is elegance as technique rather than revelation. A book composed by a master, admired for his intelligence, poise, and singular perspective on history, exile, and selfhood.

Rushdie is, quite simply, too good at writing. So good, in fact, that it becomes difficult to tell whether my lack of connection is a failure of the book or of my own reading position. It may be that I am too young, or too geographically and culturally removed from its settings and preoccupations, to feel the full emotional charge. That may well be true. But it doesn’t change the outcome: the book did not move me.

A Master at Work — and at Ease

From this angle, The Eleventh Hour reads like an excellent author going through the motions. All the machinery of an impressive novel—or perhaps more accurately, a hybrid of novel and story collection—is present and impeccably oiled. There is detail, rich characterization, the interplay of lives across time and place. There are clever formal gestures, like framing a story as a found manuscript, and the familiar Rushdie pleasures of layered narratives and heady monologues.

Nothing here is sloppy. Nothing here is careless. And yet, very little feels urgent.

What the Book Is About

If the book can be boiled down to a single word, that word is age. Aging bodies, aging nations, aging memories, aging selves. That such a reduction is possible feels, from this vantage point, like a rare misstep for a Booker-winning author. The theme is clear but not newly illuminated. There are surprisingly few moments that explore the depth and strangeness of aging in ways that feel either formally daring or emotionally bracing.

One of the strongest scenes is also one of the simplest. Two old men—opposites in temperament and biography but mirrors in spirit—treat their journey to the pension office as their last great adventure. The task becomes a repository for their dignity, a final test of relevance and agency. It’s charming, genuinely so.

But charm is where the moment ends.

Small Moments, Light Footprints

The book is filled with scenes like this: small, humane, and lightly touching. They arrive, please, and then drift away. They rarely accumulate into something heavier or more lasting. The emotional throughline is thin, and the stories, while technically connected, feel spiritually isolated from one another. They do not echo loudly across the book. They do not insist on being remembered.

This is the central problem. The Eleventh Hour does not offend, challenge, or demand. It doesn’t excite or deeply enrich. It passes through the mind with grace, but without leaving a bruise, a mark, or even much of a residue.

Elegance Without Risk

There is a sense that Rushdie knows exactly how to do all of this—and therefore no longer feels the need to surprise himself. The prose is confident, polished, and unmistakably his, but it rarely takes risks. The book feels less like a confrontation with mortality than a calm inventory of it.

That calm may resonate deeply with readers who see their own lives reflected in its rhythms and concerns. For others, it may register as distance. Admiration replaces attachment. Respect stands in for love.

Final Thoughts

The Eleventh Hour is not a bad book. Far from it. It is the work of a great writer operating at a high, comfortable level of craft. But comfort is its limitation. This is Rushdie writing from experience rather than discovery, wisdom rather than wonder.

There is beauty here, and intelligence, and moments of genuine warmth. What’s missing is the feeling that any of it had to be written now, in this way, with this urgency. In the end, the book feels less like a final reckoning and more like a graceful, forgettable coda.