Zadie Smith is fifty years old, David Foster Wallace was forty six. Throughout her career, Smith has been called a DFW acolyte. She writes detailed, passionate, didactic, yet charmingly conversational and friendly essays. Like Foster Wallace, she strikes that careful balance between academic and intimate. You can tell that there’s a strong desire there to be both likeable and a know-it-all, to do it all, to be a museum tour guide.

In Dead and Alive, Smith opens the book with this idea. That a collection of essays is like a guided tour through a museum. Through the book, Smith guides you through some favourite works, artists, and chews up the scenery with you along the way. She makes for a lively, engaging museum guide; The paintings look better when she’s around, and she continues to wear her DFW badge on her sleeve with her occasional, conversational footnotes.

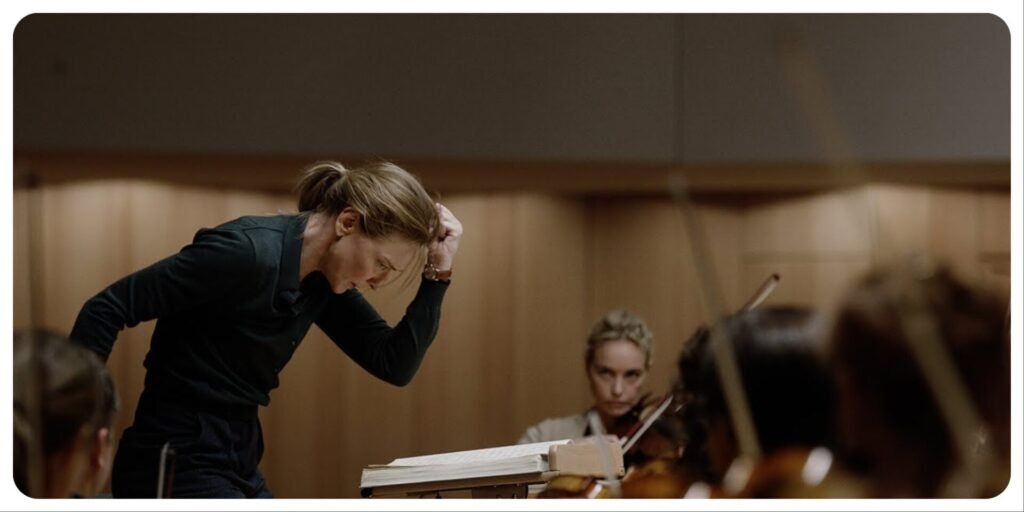

I’ve never thought of a story collection like that before, as a portable gallery, but it’s apt. Dead and Alive has five sections: Eyeballing, Considering, Reconsidering, Mourning, and Confessing. Like a museum, you can start at the exhibit closest, or walk to the one that catches your eye. It’s so unlike the snatches and skim reads that so often happen from your phone, the clicking on headlines only to read half of “Zadie Smith’s Pulitzer finalist review of Tar” before deciding to go watch the movie instead (only for it to turn out that you like the review more than the film).

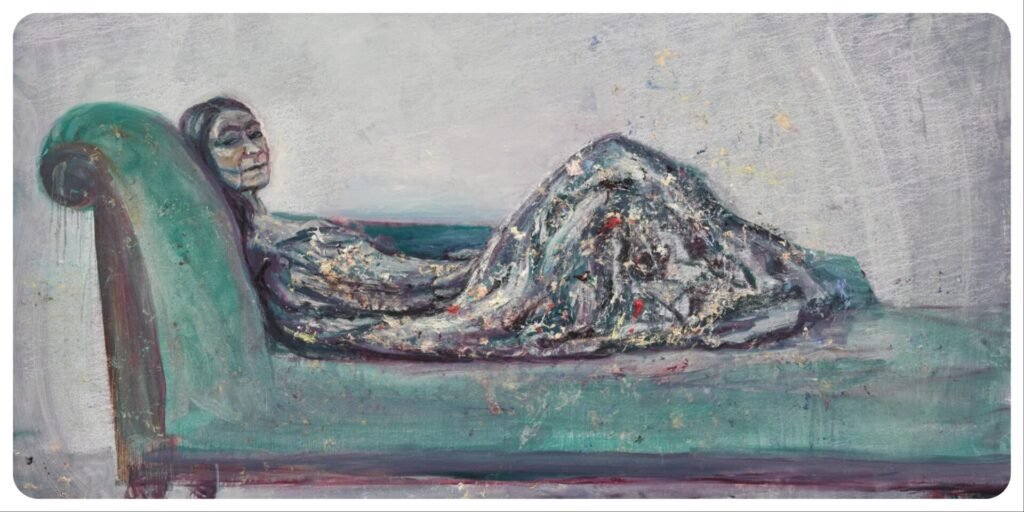

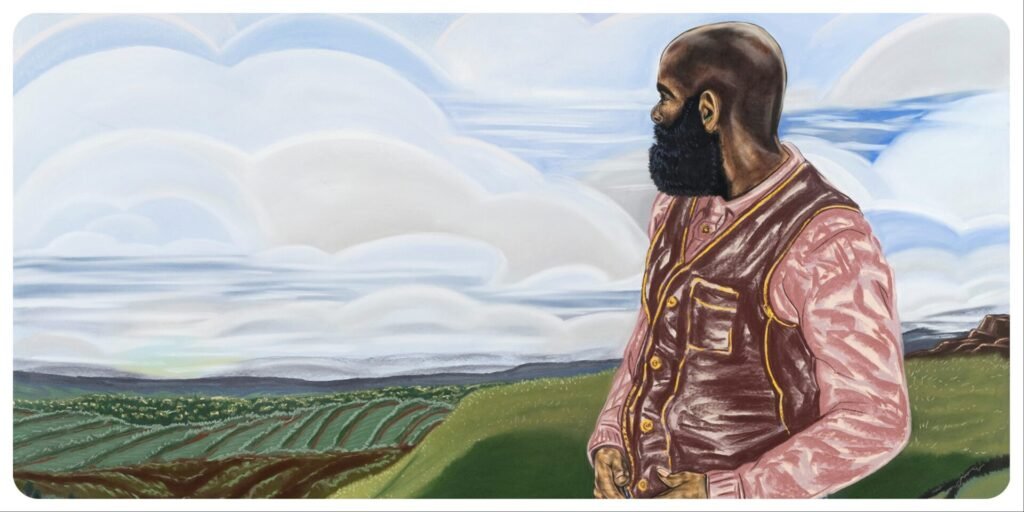

Dead and Alive gives you this choice– to play around and find pieces you like, or to come back when you’ve seen or read the works in question– but it’s Smith’s writer’s voice that makes it stand out as an experience. She’s a likeable know-it-all to be entertained and educated by as you walk through the art and exhibits. You spend time with her through the book and become a close confidant, like David Foster Wallace. Smith has that rare talent to interest you in topics you’ve never even considered. I don’t eat lobster, and definitely don’t go to the Maine Lobster Festival in my spare time, but DFW’s Consider the Lobster has given me strong feelings about both. The same goes for Todd Haynes’ Tar, or the life of Celia Paul, or some AI video that Trump made about his future for Gaza.

Of course, like any tour guide, Zadie Smith isn’t infallible. She’s taken fire from The Guardian for being too non-commital in her piece about Gaza (which she’s apparently amended a little in this version), but to force firm beliefs out of her would defeat the point. She’s a pleasant, clever companion to appreciate art and nuance with. Lectures and grandstanding and even heroic speeches peep from the cracks here and there–there is a part in the Didion piece about writers being secret bullies, imposing their words and thoughts on others, and you can tell that Smith loves and lives by this concept– but the book is best when she keeps a leash on that, maintains the friendly aura of a museum tour guide.

So, that’s all to say that it’s nice to read an essay collection that doesn’t jump around too much. One that you can open at any essay, maybe any page, and feel like you’re enjoying art, expanding your horizons, and doing it alongside a good pal.

P.S. It’s funny that she has her back turned to us on the cover, when she is trying to be our friend in the text, but maybe the idea is for it to look like the reader is talking with her? That’d be cute.