This article contains spoilers for “One Battle After Another,” now in theaters.

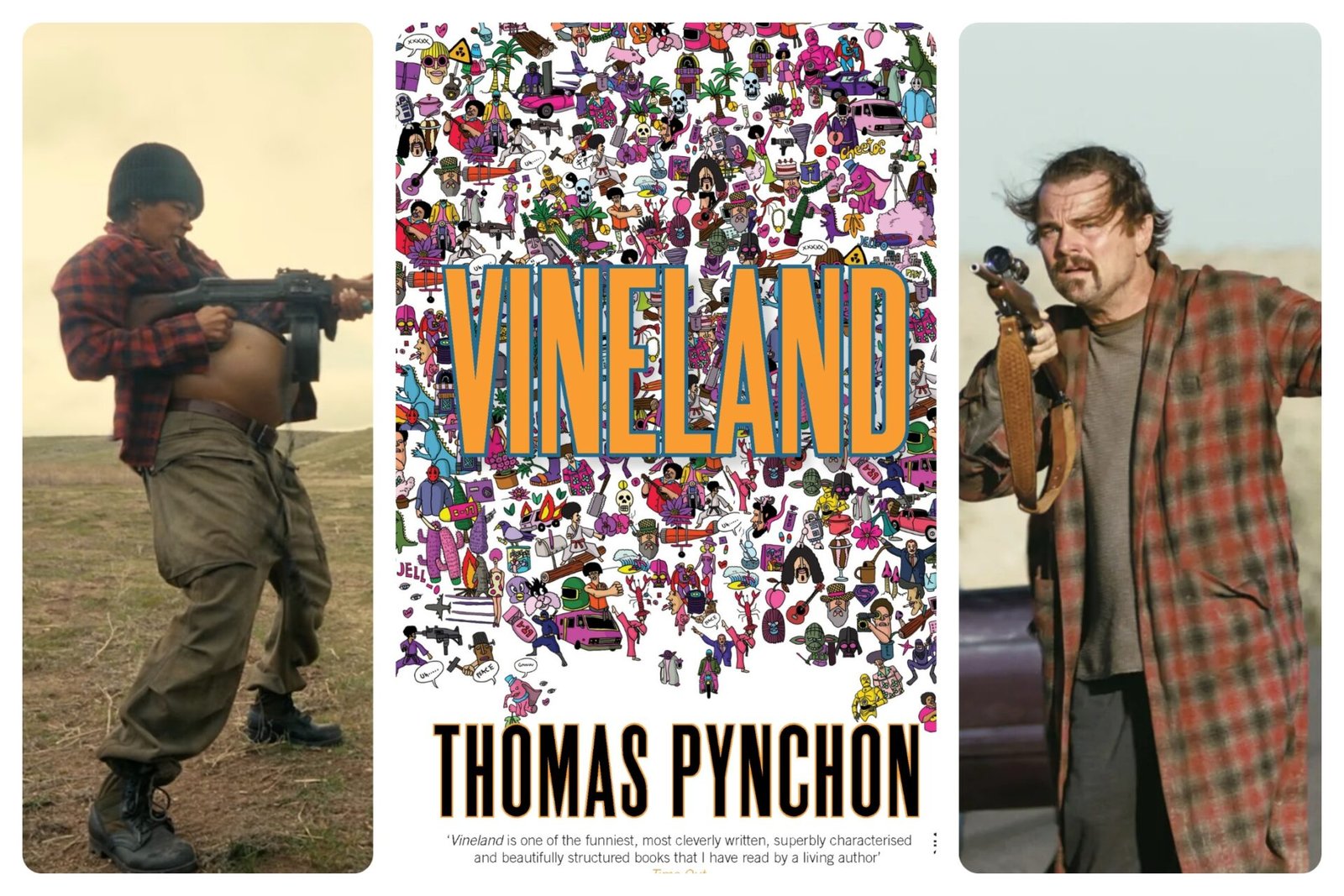

Ever since One Battle After Another entered development, rumors swirled that Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film would be based on Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland. The director, a long-time admirer of Pynchon (he previously adapted Inherent Vice in 2014), has often spoken of a desire to bring Vineland to the screen. According to The Film Stage, during a Q&A after an early screening of One Battle After Another, Anderson conceded, “I struggled for years to try to adapt it.”

Over time, the idea of a faithful Vineland adaptation waxed and waned as the film’s shape evolved. Now that One Battle After Another is in theaters, those brave enough to tackle Pynchon’s labyrinthine text can begin to map the overlaps — and the omissions.

Credits and the “Inspired by” Caveat

In a similar vein to PTA’s other films, There Will Be Blood and The Master, the film is“Inspired by the novel Vineland by Thomas Pynchon” rather than written by. As he told audiences in the Q&A, “I loved that book … but the problem with loving a book so much when you go to adapt it is that you have to be much rougher on the book. You have to kind of not be gentle.”

So though the film does carry the bones of Vineland, it’s been given a new body in the modern age. That said, there are more than a few subtle Pychonism beyond the obvious, like a mention of banana pancakes, a key symbol in Gravity’s Rainbow1.

“Danger’s over, Banana Breakfast is saved.” ― Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

Characters

Only The Core Characters Remain

The main four characters of the film lead the book, with the superwoman DL Chastain (ninja, feminist, badass) being left out.

- Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio) is Pynchon’s Zoyd Wheeler: an ex-revolutionary now transfenestration artist living off mental disability checks.

- Bob’s daughter Willa Ferguson (Chase Infiniti) is Prairie Wheeler, a hippie girl who struggles to comprehend the legacy of her parents.

- Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), the estranged mother and former radical, corresponds to Frenesi Gates, generational feminist radical.

- The antagonist Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn) is the most similar to ultra-competent agent Brock Vond in Pynchon’s novel.

Practically every other character in the film is unique, or only vaguely similar, the nuns being one of the exceptions. Benicio Del Toro’s sensei character could be called an updated Hector Zuniga, but the book’s Hector is slimy and not at all trustworthy while Sensei Sergio St. Carlos is among the most competent and admirable characters in the film.

Plot

A Straight Path Through The Labyrinth

Even though One Battle After Another is convoluted for an action/thriller, it’s far, far more simple than Vineland. The main throughline remains: an ex-revolutionary is drawn back into conflict when his daughter is endangered by a former enemy. But their narrative structures diverge sharply.

In the film,

Bob must rescue Willa, while she uncovers the political and personal history that binds them. The action unfolds more linearly: an inciting event, chase/rescue arcs, and a final confrontation.

In the novel,

once Prairie is taken, Zoyd’s presence fades from the foreground. The narrative shifts heavily into flashbacks, digressions, and meditations — Prairie’s investigation into Frenesi’s past, the collapse of the revolutionary milieu, and tangled government conspiracies. Only later does Zoyd reemerge, but the resolution remains ambiguous.

In Vineland’s denouement, the chase ends when the government abruptly withdraws funding for Vond’s pursuit; confronted with losing control of his helicopter, he crashes, leaving Prairie free but stranded in wilderness. It is a resolution born of contingency rather than closure, fitting for Pynchon’s skeptical worldview. By contrast, Anderson grants One Battle After Another a more emotionally satisfying outcome: Willa fights to reclaim her agency and reunites with Bob (now altered by the ordeal). Where Pynchon embraces ambiguity, the film leans toward catharsis.

Worlds and Tone

Satirical Surrealism vs. Grounded Paranoia

A major shift lies in tone and world-building. Vineland inhabits a semi-altered reality: southern California is imagined to have seceded in the 1960s, and the novel’s “revolutionaries” were a radical film collective dedicated to exposing fascism through cinematic means. The federal government, in turn, wages literal war on drugs, deploying cinema as a political weapon. Pynchon’s setting is a satirical exaggeration of late-20th-century America: the decline of the 1960s counterculture, the ascendancy of Reagan-era conservatism, and the media’s complicity in cultural hegemony.

Anderson, by contrast, largely discards the more absurdist, alternate-reality trappings. One Battle After Another presents a world that feels contemporary (or slightly future-leaning), rather than allegorically warped. Federal raids, immigration enforcement, racial politics, and surveillance dominate the conflict, giving the story pungent resonance for the present moment. The film retains pockets of weirdness, a secret society of white supremacists called the “Christmas Adventurers Club,” for example, but these elements are less pervasive or structurally foundational than in Pynchon’s universe.

The 16-year leap in the film gives some nod to the generational shift that Vineland explores, but Anderson never fully commits to a dialectical opposition between two eras (as Pynchon often does). Instead, the film collapses past, present, and political myth into a single heightened now. In this way, One Battle After Another is less allegorical and more visceral, trading symbolic layering for immediacy.

What Was Cut, What Was Compressed, What Was Invented

Because Anderson is working from inspiration rather than faithful adaptation, many elements of Vineland are excised, simplified, or merged:

- The “Thanatoids” and The Tube. In Vineland, Pynchon introduces the concept of “Thanatoids,” beings who are dead in life, and The Tube, a kind of mediated afterlife in television. These more metaphysical threads are absent from One Battle After Another.

- Nonlinear digressions and tonal shifts. The novel often wanders into extended subplots, digressions, and self-reflexive commentary. These are largely stripped out or collapsed in the film.

- Alternate California / Secession. The book’s speculative twist that southern California seceded is not present in the film.

- Multiple minor characters and networks. Vineland is densely populated with peripheral figures, cons piratorial groups, revolutionary collectives, and media agencies. Many of these are omitted or combined in Anderson’s version for narrative economy.

- Ambiguity over closure. As noted, Pynchon leaves resolution deliberately open; Anderson offers more conventional closure.

- Temporal framing and flashbacks. The novel’s heavy reliance on flashbacks and investigation is minimized in the film, which opts for a more forward-moving structure.

- Shifts in character motivations or morality. In the film, Perfidia remains ideologically committed and is less of a turncoat than Frenesi in the novel; Lockjaw is more villainous, less morally ambiguous than Vond in Vineland.

At the same time, Anderson adds or reconceives:

- The film’s framing is more overtly political in a modern sense: immigration, surveillance, militarization.

- Emotional arcs are heightened: characters’ internal struggles are foregrounded more than Pynchon would typically allow.

- The chase/action-thriller elements are amplified.

- Some invented plot devices (e.g. cryptic passwords, encrypted radical networks) serve cinematic momentum more than thematic depth.

Why These Changes Matter

A mix of both sacrifices to the rigours of film adaptation, and the taste of Anderson, Pynchon’s richness and nonlinear depth resist straightforward cinematic translation provide fertile soil for Anderson to grow his own film from, rather than a sculpture to paint on canvas. To render Vineland into a three-hour film would arguably demand a different medium, and even a mini-series would struggle.

Anderson’s solution is to “steal”, as he puts it, the elements that most resonated with him (character, conflict, tone) and discard or transform what would be unwieldy for the screen.

In doing so, Anderson produces a film that stands in conversation with Vineland, echoing its concerns over generational betrayal, the collapse of idealism, and the machinery of culture, while reconfiguring them for a more emotionally accessible, politically timely format.

Conclusion

One Battle After Another is not a strict adaptation of Vineland, but that was never the intention. Anderson has acknowledged that his love for the novel made a literal adaptation feel too precious; instead, he opted for a rougher, more excised approach. What remains is a film that preserves Vineland’s emotional core, a haunted father, a daughter caught between extremes, a revolutionary impulse undone, while shedding many of its more eccentric, nonlinear excesses.

For viewers familiar with Pynchon, the pleasure lies in spotting the echoes: Bob as Zoyd, Willa as Prairie, Lockjaw as Vond, the ruptured ideological inheritance. But the film also invites newcomers into its own world, where the stakes feel urgent, the worldview darker, and the action more immediate. In grafting Pynchon’s skeleton onto a leaner cinematic frame, Anderson renders Vineland’s spectral energy into a different beast, one that punches, weeps, and resists all at once.