Somewhere in between pausing a game and pressing the screenshot button, something has started to happen. Players are taking it all in, considering and composing shots. Angling. Adjusting. Waiting for the perfect animation frame. And increasingly, it’s becoming art.

Virtual photography—or in-game photography, depending on who you ask—has become an unexpectedly serious pursuit for a growing number of players. What started as a niche hobby among modders has evolved into a kind of ambient visual culture: screenshots that look like movie stills, self-portraits taken in apocalyptic ruins, sweeping landscape shots worthy of a National Geographic spread—if National Geographic covered Elden Ring.

But does that make it art? Or is it just a new form of fan expression with a very good sense of lighting?

A New Kind of Looking

At first glance, calling screenshots “art” might feel like a stretch. After all, the worlds being photographed weren’t built by the photographer. The characters, environments, and lighting systems are all part of someone else’s creative work. But then again—so is a city. So is a forest. Street photographers and landscape artists have long made meaning by finding new ways to see what’s already there.

Virtual photographers work similarly. In many games, they wait for the weather to shift, or the light to change, or a character to pause mid-motion. Some use built-in photo modes. Others rely on community-made camera tools that allow for more cinematic control—free camera movement, focal depth, field of view. They’re not playing the game, exactly. They’re observing it. And sometimes, reinterpreting it.

What makes this practice interesting isn’t the novelty—it’s the intent. A screenshot might freeze a beautiful moment. A virtual photograph tries to say something with it.

Where It All Started

Before photo modes were common, the scene existed in a much scrappier form. Websites like Dead End Thrills, founded by Duncan Harris, showcased stills taken from PC games—using mods, hacks, and a fair amount of patience—to celebrate the artistry hiding in plain sight. It wasn’t about action shots or killstreaks. It was about light falling on stone, fog rolling in over a cliff, a single figure standing at the edge of something unknowable.

These early practitioners treated video games less like digital playgrounds and more like virtual landscapes worth documenting. The goal wasn’t to show what the game could do, but what you could see if you slowed down.

Today, artists like Petri Levälahti (also known as Berduu) have gone professional, crafting in-engine stills for studios like EA DICE. He got his start as a hobbyist on Flickr, experimenting with mods and learning from other screenshot artists. Through the community, he was hired freelance for Battlefield 4, which lead to a full-time position. “Working in-engine is more about making the screenshot than taking it,” he’s said. It’s not about capturing what happens—it’s about staging what might.

Why It Works

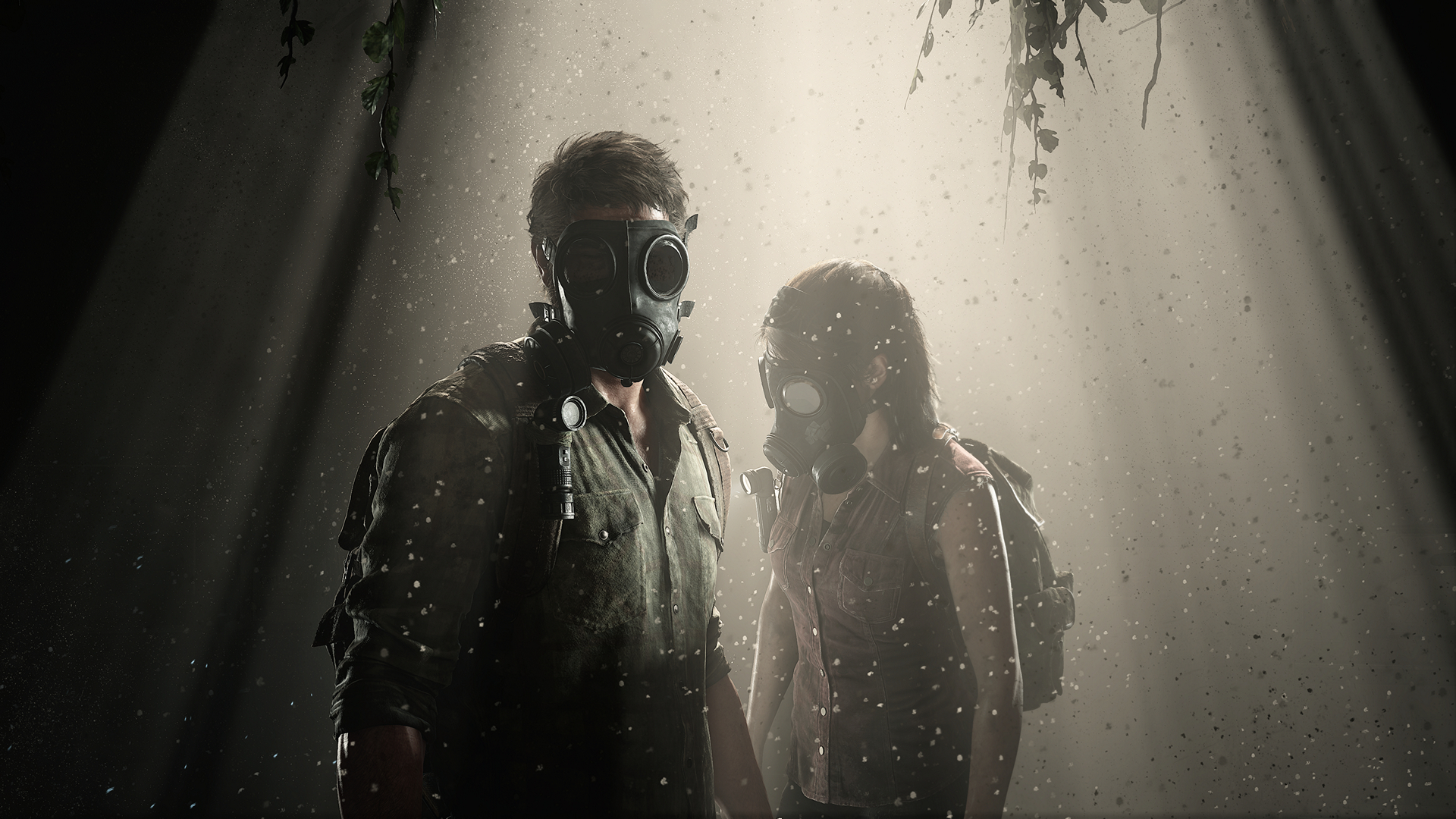

What makes these images resonate? It might be the tension between what’s real and what isn’t. We know these aren’t photographs. They’re not snapshots of a lived moment. And yet, they feel familiar. You don’t need to have played The Last of Us to feel something from an image of Ellie caught in the crosslight. You don’t need to recognize the planet in Mass Effect to sense a mood.

A lot of it comes down to mood, actually. While many of these shots are beautiful, they also carry a kind of emotional ambiguity—a loneliness, a stillness, a smallness in the face of something massive. They’re often the exact opposite of how we usually experience games: not urgent, but quiet.

Of course, some of this might just be good visual design doing the heavy lifting. Games like Ghost of Tsushima, Control, or Red Dead Redemption 2 are already cinematic. Part of what makes in-game photography feel like art is the artistry of the games themselves. But maybe that’s the point. These photographers aren’t creating a new medium—they’re reframing an existing one.

Still Life in a Moving Medium

There’s also something slightly absurd about all this. Spending an hour composing an image no one may ever see? It’s obsessive, yes. But it also reflects something deeper: a shift in how players relate to games.

This isn’t just about documenting gameplay. It’s about looking, creating. The kind of attention that’s rooted in a desire for more, to reach higher.

And maybe that’s enough to call it art.

Or maybe it’s just a new kind of fandom—one that’s evolved past quests, KDAs, and 100% completions. One that craves a unique, freeform experience that allows for true personal expression and a deeper engagement with the works provided by the game’s artists.

Either way, it’s worth watching as it’s an art form on the grow.

To learn more, check out The Photo Mode, the fandom’s first magazine which is free to download on their site. The site also has a resource list that shares the links to the hashtags and forums that other fans/artists/hobbists use too. And to see what it’s like on the other side of the fandom, virtual photography as a profession, check out Petri Levälahti DiCE works.

Gallery